We spent most of our Sunday in Westchester County, where we attended the funeral of a friend’s father who had passed away, very unexpectedly, at the age of 72. I’d never met the man and knew very little of him before the service, but over the course of the day; the memorial, the burial and the reception; grew to feel an easy admiration and love for him and the family he so clearly adored.

He had come to America as a child, through Ellis Island after World War 2, and forged his own path through life; studying astrophysics in college, then becoming an entrepreneur; a book seller and then a book binder. He was a boxer. He wrote poetry and concertos and spontaneously composed songs to embarrass his kids. He raised four of them and cared for his elderly mother, who tragically outlived him. Above all else, he was a free spirit and had a passion for adventure, and it was easy to understand why he was so beloved by his children, his family and friends.

I felt like I understood him, like he could have been a friend of mine; a writer, a musician, a dad. And a baseball fan. He deeply loved baseball.

Having settled with his family in upper Manhattan as a kid, he had grown up near the old Polo Grounds, where Willie Mays and the New York Giants held court before they split New York City to set up stakes on the West Coast in 1957, breaking the hearts of thousands of local fans. His allegiance shifted to the Mets when they arrived five years later, taking up residence at the Polo Grounds for two years before finding a permanent home in Queens in 1964, and he became a die-hard fanatic, making annual pilgrimages to their spring training facility in Port St. Lucie, Florida, and attending home games at Shea Stadium and later, City Field.

I grew up with the Red Sox, a team that had repeatedly destroyed my faith from the time I was six years old, from 1978 until late October 2004, when, in an unmatched moment of catharsis for long suffering New England-born fans everywhere, they finally won their first World Series in 86 years. I won’t go too far down that rabbit hole here, as that’s at least an entire essay unto itself, but suffice to say, for 40 years, the Red Sox have belonged to me, their successes and their many failures, in the same way the Mets no doubt belonged to our friend’s father. A team’s story becomes our story and we pass those stories down to our kids, our partners, whoever will listen. We follow the slowly developing narratives on tv, radio, and the internet, through games, boxscores, interviews and newspaper columns. As a kid, I memorized stat lines off the back of baseball cards, internalized them, and in the winter, I’d spread out the Sunday Boston Globe on the living room floor to study Peter Gammons’ team notes and transaction rumors. Now, there are routine check-ins on message boards, blog updates, a 24 hour news cycle running throughout the season and off-season. I used to believe it was a New England thing, this obsession, this love for such an uncontrollable and disappointing thing as a baseball team, the brutal winters leaving us little recourse but to dream of summers and the Red Sox. Living in Brooklyn now, I can see this is how it is everywhere. I can see there is this thread that connects us, an understanding between fans of this game. We may hate each others’ teams, but there is a mutual recognition of each others’ passion and each others’ pain. And on this particular Sunday, though the Mets season had long since ended in disappointment, their great pitching undone by an anemic batting lineup, the Red Sox, my Red Sox, happened to be preparing for game five of the World Series, going toe to toe with that other expatriate baseball team from New York City, the Los Angeles Dodgers.

I left Westchester around 6 pm, said goodbye to my fiance, a Yankee fan in her own right, fought through some Sunday traffic in the Bronx, picked up the dog from the puppy-sitter, dropped off my daughter’s backpack at her mom’s house, and made it home just in time to see Mookie Betts coming to the plate for the first pitch.

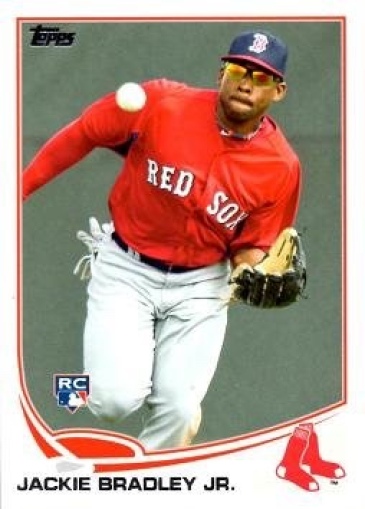

The Red Sox had built a commanding 3-1 series lead heading into Sunday night’s game, and just needed one more win for the championship. They were the clear favorites entering this year’s Fall Classic, having won 108 games during the regular season, a franchise record and the highest single season wins total since the 2001 Seattle Mariners won 116 games before being defeated by the New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series that year. The 108 wins matched some historically great teams’ single season records, including the 1975 Cincinnati Reds that featured Johnny Bench, Pete Rose and Joe Morgan, the 1970 Earl Weaver led Baltimore Orioles, and the 1986 New York Mets, who broke the hearts of New Englanders everywhere that year when, through a tragic comedy of bloop singles and errors, beat the Sox in the World Series that year. This year, we were fielding a juggernaut of sorts, a team built around a remarkably air tight outfield defense that featured a trio of likable young players, Andrew Benintendi, Jackie Bradley, Jr. and Mookie Betts, and an unrelenting offense that led all of Major League Baseball in runs scored, hits, doubles, total bases, runs batted in, batting average, on-base percentage and slugging percentage. They’d also finished 9th in the league in home runs and third in stolen bases. They were really good, and the aforementioned Betts had developed into one of the prominent new faces of the league over the course of the season, a pint-sized version of Willie Mays, an MVP candidate who hit for power and average and played the game with hustle and joy. The pitching was solid as well, led by a pair of tall southpaws, perennial Cy Young candidate Chris Sale and David Price, an excellent pitcher in his own right who had been, to this point, an annual lock to win 15 or more games during the regular season, then flame out in the postseason.

The Dodgers came into the series a talented but star-crossed team. They’d steamrolled through the regular season in 2017, only to lose the World Series in seven games to the Houston Astros, but struggled this year, barely squeaking into the playoffs, winning their division in a tie-breaker with the Colorado Rockies on the final day of the regular season. They had lost their best positional player, shortstop Corey Seager, to an elbow injury early in the year and replaced him, through a midseason trade with the Baltimore Orioles, with Manny Machado, a supremely gifted infielder, a stat geek’s dream who hits for a ton of power but seems prone to lethargy in the field. For all his talents, Machado often looks lazy at shortstop and rarely hustles on the base paths. In game three of the of the series, batting against Sox right-handed starter Rick Porcello, he hit a long fly ball to left field that looked like it may carry out for a home run. Assuming a slow home run trot out of the batter’s box, the ball stayed in play, bouncing off the left field wall and Machado, instead of taking an easy double, jogged his way to a single.

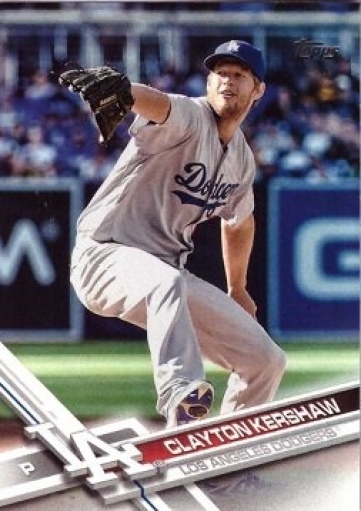

Lefty Clayton Kershaw, a generationally great starting pitcher, led a solid Dodgers pitching staff, though he entered October showing some signs of physical decline. His fastball, which regularly touched 96 mph in 2016, was generally sitting at around 90 mph during this series, forcing him to rely heavily on breaking pitches and changeups to get outs, and he’d had a difficult time handling the Sox hitters in game 1.

The Dodgers as a team, fronted by by manager and former Red Sox hero Dave Roberts, relied heavily on advanced baseball analytics in their decision making, putting strict limitations on how many times a starting pitcher might be allowed to move through an opponents’ batting order, and shuffling some of their best regular starters in and out of the lineup based on right-handed and left-handed splits. While this may have served them well during the regular season, these strategies seemed to cast them as their own worst enemy in the games leading up to Sunday night. Depending on pitching matchups, some of their best players were left sitting on the bench, and in Saturday night’s game four, they inexplicably pulled 36 year-old left-handed starter Rich Hill, who, having allowed only a single hit, had pitched the Dodgers to a 4-0 lead with one out in the seventh inning. Befuddled by Hill, the Sox hitters took advantage of the poorly advised pitching change and proceeded to pounce on a string of Dodger relief pitchers, scoring 9 runs over the last 2 and a third innings to win the game.

Roberts’ managing style was a stark contrast to Sox manager Alex Cora, who seemed to push his team more aggressively, more by feel, giving players an opportunity to shine in roles and situations they may have previously been unaccustomed to. Game five starting pitcher, David Price had started game two, pitched 2/3 of an inning in relief in game three on just two days’ rest, and had been warming up in the bullpen, in case he was needed for game four, an unheard of amount of work for a starting pitcher. Catcher Christian Vasquez played some innings at first base. Starter Nathan Eovaldi, acquired through a mid-season trade with Tampa Bay, had been shifted to relief ace, pitching highly effective, high leverage innings in games one and two and an unforgettable six shutout innings in game three, an 18 inning, seven-and-a-half hour epic, before surrendering the winning home run to the Dodgers’ Max Muncy in the bottom of the 18th, sometime after 4 am east coast time.

*****

There had been some beautiful memories shared in the Memorial early on Sunday, none more resonant than when our friend’s brother expressed, in saddened disbelief, that he always thought there would be another ballgame to go to with his dad, another opportunity to throw a ball around the yard with him.

I used to pitch to my dad in the back yard. I’d have kept him out there forever with me if I could. Exhausted by work, he was usually good for 30 or 40 minutes of throwing the ball back and forth with me. He set up a practice pitching target for me to throw to when he wasn’t around, a pliable net with a painted strike zone that would rebound the baseball back to me after each pitch. From March through November, I’d throw to that thing, imagining I was pitching in the World Series. Or, I’d become a hitter, tossing balls up in the air to myself and smacking them with an aluminum Easton bat, imagining the balls that carried into the trees at the far end of our lawn were home runs. But I was never very good nor did I know how to be very good. I played Little League baseball for a team sponsored by a local company named “Herman Shoe.” Our uniforms were bright orange with the initials “HS” printed in large black letters on our caps. Around the league, the acronym was understood by kids to mean “Horse Shit.” I was a pitcher, and I had the unique distinction of having thrown a no-hitter, only to lose 6-0 because I’d walked at least 8 batters and we’d committed about a half-dozen errors in the field. I pitched every inning of every game. We won once. We lost over and over and over again.

“That’s why he was here, to surrender himself to longing, to listen to his host recite the anecdotal texts, all the passed-down stories of bonehead plays and swirling brawls, the pitching duels that carried into twilight, stories that Marvin had been collecting for half a century–the deep eros of memory that separates baseball from other sports.”

– Don DeLillo, “Underworld”

Baseball is such a simple, elegant game. Throw, hit, catch, run. At it’s core, it’s largely unchanged from the way it was played in it’s original conception during the 19th century. In a world driven by constant and aggressive change, the essence of our national pastime has remained slow and pastoral. It’s timeless, and through this timelessness it connects its fans from generation to generation. Throwing a ball around in the backyard with your parent or buddy is basically the same experience it was 75 years ago. At the ballpark, whether it’s Fenway or Citi Field, one has essentially the same experience of the actual game as one had 100 years ago. I remember my dad taking me to my first Sox game against the Milwaukee Brewers in 1983, the excitement of seeing Fenway Park for the first time, sitting through a late inning rain delay and then watching Jim Rice, my favorite player, hit a home run in the eighth inning to provide the go-ahead, winning run. My daughter’s first game was at Yankee Stadium, where I’d taken her to see the Sox play in 2005. She thrilled just as I did as we were coming out of the tunnel, the great wide expanse of outfield grass appearing in the light to her for the first time. There was soda, popcorn, the languid pace of the game inviting the sharing of food and stories between pitches and innings. I told her about my dad waking me up on a school night to watch Roger Clemens break the single-game strikeout record against the Seattle Mariners in 1986, about Dwight Evans’s crouched batting stance that the kids in my neighborhood all tried to imitate, about how I cried when the Sox failed to tender a contract to Carlton Fisk, the greatest catcher in baseball, and he left us for Chicago, and how we’d won the whole thing last year, the first time we’d won it in 86 years, and it took the most improbable comeback in history to do it. We chatted it up with Yankees fans, who were amused by the adorable four year-old who’d come to their house in a kids’ sized Red Sox hat to boo their players. And then Manny Ramirez, her favorite player at the time, homered, and we won.

*****

The New York Mets won 108 games in 1986 and needed a miracle to beat the Red Sox. In game 6, with Boston holding a three games to two series lead, the two teams played to a tie, ending the 9th inning at Shea Stadium with the score 3-3. In the top of the 10th, with the Red Sox batting, Dave Henderson, a newly minted postseason hero who had already saved the Sox season with a go-ahead, 9th inning home run in game five of the ALCS against the Angels, lead off with another home run to give the Sox a 4-3 lead. After two quick strikeouts, third baseman Wade Boggs, the best pure hitter in baseball, doubled to left field and came home on second baseman Marty Barrett‘s single, stretching the lead to 5-3. I was watching this game with my dad and a couple of his buddies. There was giddiness and celebration in our home heading into the bottom of the 10th inning. We were going to win. Calvin Schiraldi, a relief pitcher who had been a dependable hero throughout the playoffs and World Series, was pitching the bottom of the 10th for us and got the first two hitters, Wally Backman and Keith Hernandez, to fly out. There was a congratulatory announcement shown on the Shea Stadium scoreboard, something like, “Congratulations Red Sox, 1986 World Champions” and then, like some weird nightmare, it all came apart. A single by catcher Gary Carter, a single by Kevin Mitchell, a single by Ray Knight. Schiraldi was coming undone. The Mets had cut the lead to 5-4. Bob Stanley, our fattest and most beleaguered relief pitcher, was brought in to face Mookie Wilson, and on the 6th or 7th pitch of the epic at-bat, uncorked a wild pitch, allowing Mitchell to score from third base and tie the game at 5. Ray Knight moved to second base, then scored the winning run when Wilson dribbled a ground ball through the legs of first baseman Bill Buckner, who had been playing the entire series on two bum ankles. The ball rolled helplessly into short right field as Knight crossed the plate. Game over.

Evidently, there was joy in New York City that night. I watched it on tv. For Mets fans everywhere, including, I imagine, our friend’s father, Game 6 and the images of the ball rolling under Buckner’s glove and through his wickets, of Ray Knight scoring the winning run in disbelief, of his ecstatic teammates mobbing him at home plate, of the visiting villainous Sox impossibly choking and allowing their beloved Metropolitans to steal the game and all the momentum in that series, will shine forever in their memories like some euphoric fever dream, a rare “where were you when?” moment to be discussed passionately at the ballpark, in bars, at Christmas parties, for decades into the future. In our home, there was only stunned silence. I remember lying in my bed that night, staring up at the ceiling, defeated beyond any measure I had known before. It was an emotional defeat, a physical defeat, a spiritual defeat, a psychological defeat. The Mets had only just tied the series at 3 games apiece, but we knew better than to hope after that. Game 7 felt like a foregone conclusion. We’d lost.

“You may glory in a team triumphant, but you fall in love with a team in defeat. Losing after great striving is the story of a man, who was born to sorrow, whose sweetest songs tell of saddest thought, and who, if he is a hero, does nothing in life as becomingly as leaving it.”

Roger Kahn

There was little such drama in Sunday night’s game 5, as the Sox dispatched L.A. by a score of 5-1. Given the stakes, a potential series-clincher, David Price pitched perhaps the greatest game of his career, throwing seven innings of three-hit ball to stifle the Dodgers, allowing only a first pitch home run to leadoff hitter David Freese. Massachusetts native and Series MVP Steve Pearce, a journeyman first-baseman whose previous claim to fame had been that he’d spent bits of his career playing for each of the five American League East teams, hit a two run homer in the top of the first inning, which proved to be all the runs they’d need on this night. For good measure, he added a second home run in the eighth inning, following solo shots by Mookie Betts in the 6th and JD Martinez in the 7th. Thanks to Price, the outcome was, mercifully, never really in doubt. I watched the Fox broadcast of the game with the volume muted and the radio feed from WEEI in Boston turned up. By the seventh inning, Joe Castiglione, long-time voice of the Sox, was already discussing who might win the series MVP. There were flurries of texts exchanged between my sister, my dad and me as the game developed, and overwhelming happiness when Chris Sale struck out Manny Machado, literally bringing him to his knees as he swung and whiffed on the game’s final pitch, to finish the Series.

Since 2004, when the Red Sox ended their 86 year-old title drought, Boston has been the most successful franchise in Major League baseball, winning four championships in 15 years. There has been an embarrassment of riches, brought about by intelligent ownership and a forward-thinking personnel department, giving Sox fans a parade of stars, playoff appearances and World Series victories to enjoy. As a kid and a young adult, watching them fail and fail again, sometimes comically, sometimes tragically, I never would have dreamed such a thing. After the World Series in 1986, and after the ALCS against the feared Yankees in 2003, where Grady Little‘s managerial incompetence and Aaron Boone’s bat sent the Sox to defeat yet again, I imagined I might never see them actually win, that this all was some great spiritual lesson in suffering. And then they won. Incomprehensibly. And won again. And again. And as it turns out, I was correct, it is a lesson in suffering. Because in baseball as in life, there is always an ending, and there is always disappointment mingled with joy. Most seasons cease in failure, and when we finally get what we want and we win, we are still left wanting more.

There is a tradition I have at the conclusion of each baseball season, not too many years old, of rereading “The Green Fields of the Mind,” an essay by former baseball commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, penned at the close of the 1977 Red Sox season. For those who love and know baseball, there is an inherent symbolism in the game, it’s resurrection in spring filled with optimism, ushering in new hopes and new stories and new heroes, and it’s passing in Fall bringing a kind of sadness. Giamatti’s essay expresses this in more eloquence than I could ever hope to, so I’ll leave you with a little of it here.

“It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops. Today, October 2, a Sunday of rain and broken branches and leaf-clogged drains and slick streets, it stopped, and summer was gone.”

A. Bartlett Giamatti, “The Green Fields of the Mind”

Incredible.

LikeLike

Well, that’s beautifully put.

A few reactions …

a) Underworld is my favorite book. Obviously.

b) Delano Agency = D.A. = Dumb Assholes

LikeLiked by 1 person